By Mitch Tousley

As we approach the end of Women’s History Month, I wanted to reflect on a part of Utah’s musical history that isn’t (but ought to be) a part of our collective memory. While a college student, I took a class on Native American history and wrote a research paper about Zitkala-Sa and her involvement with a BYU professor on the creation of The Sun Dance Opera. That paper serves as the basis for the text of this article and has remained largely unedited.

It’s worth noting that the cultural descriptions of both the Indigenous and European white groups are most applicable to those alive at the time of this opera and are still broad historical generalizations. Sadly, audio of any performance of this opera does not exist, so we cannot fully grasp the music created. Included in this article are primary and secondary documents held in the Harold B. Lee Library at Brigham Young University.

Zitkala-Sa (otherwise known as Gertrude Bonnin) was a well-known writer, activist, and composer and is perhaps one of the most revered and influential Native Americans in the history of the United States. Her work as an activist is well documented, but her work as a composer and librettist is less well-known. As an activist, Zitkala-Sa worked to make the Native American experience a more accepted part of the broader American life. Her music, and in particular, The Sun Dance Opera, helped make the Native American experience more understood by the general American audience.

Music has historically functioned in many different ways across different cultures. In Europe, music used to be used almost exclusively in church services as a part of worship, but much of the famous classical music that has been preserved by conservatories and composers (from non-religious settings) comes from a performance-based culture, in which an audience gathers to watch musicians perform.

In contrast, Native American music functioned differently. The songs of Indigenous peoples often accompanied dances and other sacred rituals and were transmitted orally by elders to younger tribal members. One could view the creation of music in Native American communities less as a “music for music’s sake” approach than the classical and romantic European approach. To many Native Americans, it would be quite bizarre to pay to go see a performance of music. But for many European-Americans, it would be odd to only hear music in a functional, sacred context and not hear it in a performer-audience dynamic. This juxtaposition of musical tradition and style is one of the many challenges that faced The Sun Dance Opera musically and culturally, but that same juxtaposition made its success all the more rewarding.

In a dissertation about the life of Zitkala-Sa, Susan Domingues explains, “Gertrude Bonnin met Mormon music teacher William Hanson in 1908… Born in 1887 in Vernal, Utah, the son of Danish musicians, Hanson grew up with Indian children as playmates. He strongly desired to ‘preserve’ traditional ceremonies and music… After returning to the Uintah-Ouray reservation in 1910, Gertrude Bonnin, as ‘Zitkala-Sa,’ began collaborating with William Hanson on the creation of The Sun Dance Opera, which premiered in Vernal, Utah in 1913”. 1

Hanson’s desire to fight against the idea of the “vanishing Indian” propelled the project forward. Regarding Hanson’s motives, Catherine Smith wrote:

A major reason Hanson gave for his work on this opera (and the one following) was to preserve a rapidly vanishing culture. He was scarcely alone in his view that Native Americans were a ‘vanishing race’ at that time, for their population had declined disastrously in the nineteenth century. A romanticized image of an irretrievably ‘vanishing race’ was at the same time a popular notion in the white imagination. As the Handbook of North American Indians‘s editor remarks, “so desperate was their [the Great Basin Indian people’s] condition that White observers in the latter part of the nineteenth century predicted their imminent extinction, and some even welcomed the possibility as a solution to ‘the Indian problem.” 2

Advertisements

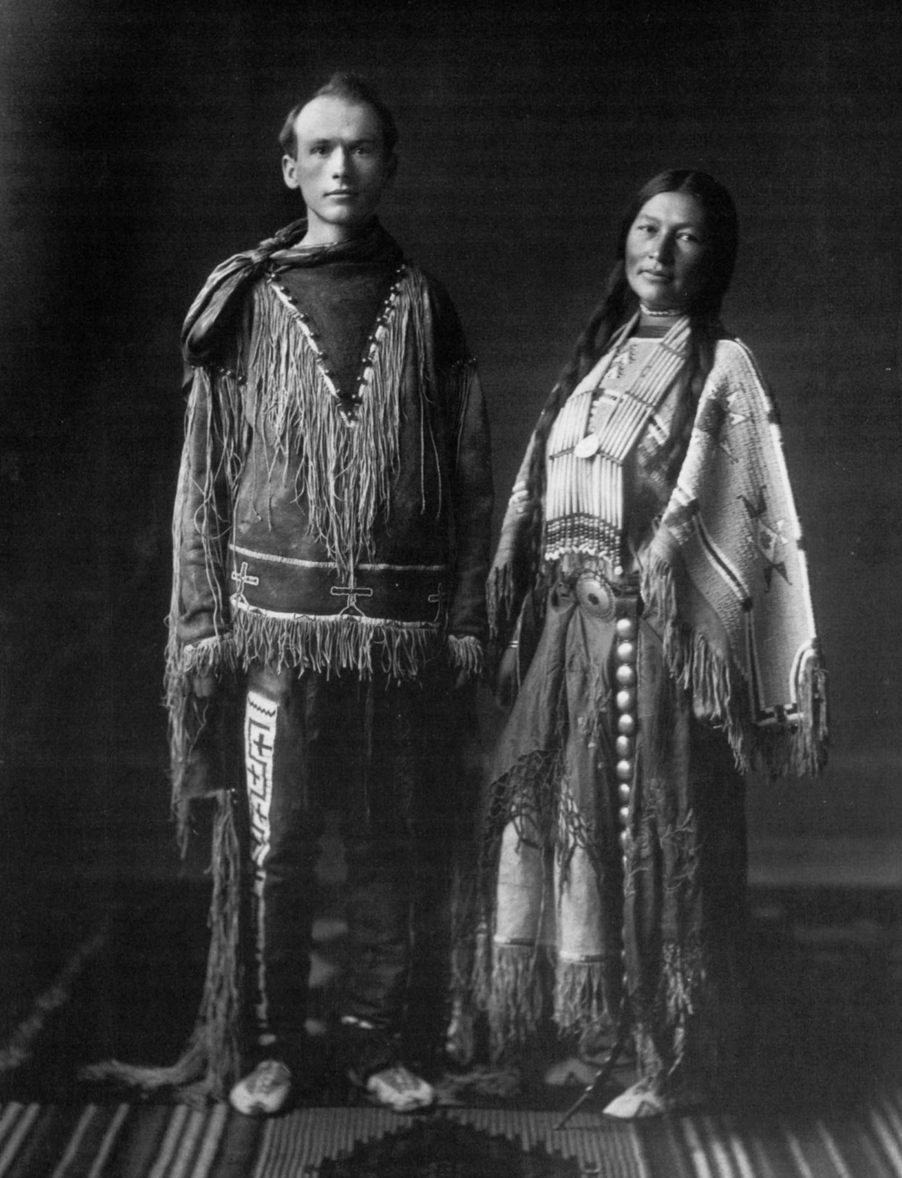

The opera these two created is the first opera written in any capacity by a Native American. Despite the difficulty of combining the musical devices of European and Native American cultures in a story that is inherently Native in its themes, Bonnin and Hanson had one cultural advantage that raised interest in their ground-breaking project: European Americans viewed Indigenous people as exotic and with a large eye of curiosity.

Before The Sun Dance Opera, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows provided white Americans with an outlet for their arm’s length interest in Natives by depicting them in broad, vaguely Great Plains-Indian inspired outfits that played Indian experiences for entertainment rather than for education. The Sun Dance would provide audience members with an authentic depiction of rituals of significance to Natives while combining them with romantic music. This musical expression of Native American themes would remind audiences of a piece like Dvorak’s New World Symphony, which borrowed folk melodies to create a piece that felt uniquely American.3

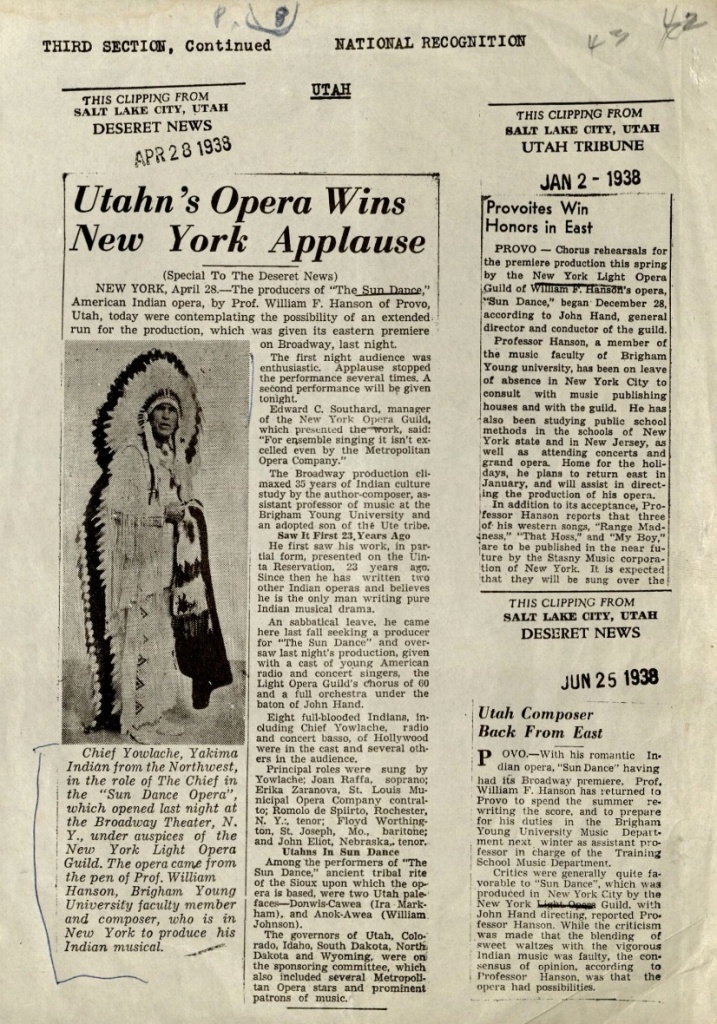

The Sun Dance Opera premiered in Utah and was met with acclaim. For its time, it was a great success in translating the authenticity of a Native American sacred experience to white audiences who had a tenuous-at-best understanding of Native American life. Years after its initial premiere and following the death of Bonnin, the opera had a run of shows in New York City that were also met with great acclaim. During the performances in New York, several of the leads were performed by urban Indians instead of white performers.4

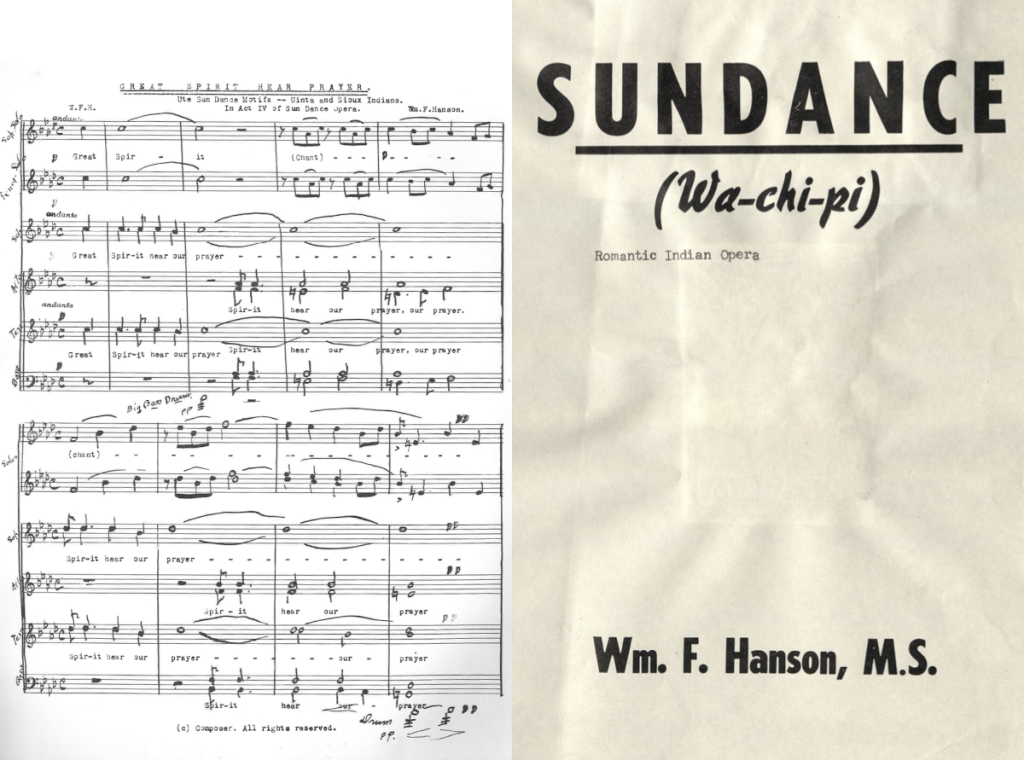

In this whole story, there is one recurring oddity. On the musical scores and many of the reviews and publications about the opera, Bonnin’s name is left excluded. William Hanson is clearly credited with his work on the opera, but primary sources leave a lot of unanswered questions about the capacity in which Bonnin herself was involved. Notice in both of the documents below that Hanson’s name is credited and Bonnin’s is nowhere to be found.

There isn’t much documentation about why Bonnin didn’t credit herself as she should have. A Native herself, author P. Jane Hafen wrote the following about why this part of Bonnin’s life isn’t well-documented:

In the context of Gertrude’s whole life, she had to make choices that many of us would not make today. The hegemonic assaults on her person, her tribe, and her culture were more direct and threatening than the cultural exploitations of Hanson and the opera. Her well-documented struggles in boarding schools and as a teacher, her fight for Indian citizenship, her campaign against peyote (despite the legal threat to tribal sovereignty), and her documentation of violence in Oklahoma during the “reign of terror” all reveal her underlying commitment to indigenous causes. Gertrude combated prejudice on fundamental levels and she responded by declaring the significance of Native cultures. It may have been beyond her imagination to consider that, in addition to the direct attempts to deprive Native peoples of their rights, there would be those who would patronizingly rob through imitation the sacred rituals, as well. The Sun Dance Opera allowed Gertrude to assert the value of her own beliefs without apparent consequence. It is also a brief representation in the whole of her creative literary and political life. Gertrude’s distancing from the opera and her apparent lack of involvement in its revival are balanced by her political and personal activities. While Hanson was musically performing, Gertrude and Raymond Bonnin were establishing land claims for various western tribes and were involved with other tribes who were implementing the Indian Reorganization/Wheeler Howard Act of 1934. Artistic expression was a luxury that paled against political imperatives and financial and family challenges that included rearing her grandchildren. Perhaps this is why she did not contest Hanson’s later self-representation as composer of the opera. Nevertheless, The Sun Dance Opera remains a fascinating duet between cultures, ideologies, and William F. Hanson and Zitkala Sa.2

The Sun Dance Opera is a remarkable achievement in the arts and culture. Despite confusion over the role that Bonnin (Zitkala-Sa) played in its inception, it is in line with her history of activism. Positive and authentic representation of Native Americans in American media wouldn’t become consistent for many decades, but the opera laid important groundwork for Natives in the arts for years to come and ought to be cherished as an important part of Utah music history.

Bibliography

- Dominguez, Susan Rose. “The Gertrude Bonnin Story: From Yankon Destiny Into American History: 1804-1938 Volume II.” Dissertation, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, 2005.

- Hafen, P. Jane. “A Cultural Duet Zitkala Ša And The Sun Dance Opera.” Great Plains Quarterly Spring 1998 (1998). https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3027&context=greatplainsquarterly.

- Hanson, William F. “Great Spirit Prayer.” Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, n.d.

- Hanson, William. “The Story of the Sun Dance Opera.” Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, n.d.

- Smith, Catherine P. “An Operatic Skeleton on the Western Frontier: Zitkala-Sa, William F. Hanson, and The Sun Dance Opera.” Women & Music; Lincoln, vol. 5, no. 1, 2001.

- “Utah’s Opera Wins New York Applause.” Deseret News. April 28, 1938.

- “‘The Sun Dance’ Romantic American Indian Opera at the Broadway Theatre, April 27th and 28th.” New York , NY: Hammond J. Mitchell, 1938. New York Light Opera Guild, Inc.